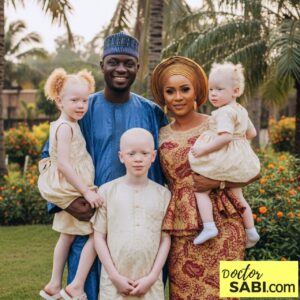

Many people ask this question out of curiosity or concern, and the simple answer I often give them is yes, it is possible. But that’s just the simple answer. For us to understand the intricacies in dwarfism and how it’s inherited by children, we need to explore the science behind it.

This post focuses on the most common type, achondroplasia, which accounts for about 70% of all dwarfism cases worldwide. We will cover what causes it, how it is inherited, the chances of different outcomes, and some important considerations for families.

What Is Dwarfism and Achondroplasia?

Dwarfism is a term for conditions that result in short stature, typically defined as an adult height of 4 feet 10 inches (147 cm) or less. For context, there are more than 400 different types of dwarfism, each with their unique causes and features. Some affect only height, while others impact health in other ways.

Achondroplasia is the most common form. It is a type of skeletal dysplasia, meaning it affects how bones grow. People with achondroplasia have average-sized torsos but shorter arms and legs. Adult men usually reach about 4 feet 4 inches (131 cm), and women about 4 feet 1 inch (124 cm). Their heads may be larger, and they might have a prominent forehead or curved spine.

This condition does not affect intelligence or lifespan in most cases. With proper medical care, people with achondroplasia lead full, independent lives.

What Causes Achondroplasia?

Achondroplasia is genetic. It results from a mutation in the FGFR3 gene, located on chromosome 4. This gene makes a protein that regulates bone growth. When this gene is mutated, it sends signals that slow down the growth of cartilage into bone, especially in the long bones of the arms and legs.

Interestingly, the mutation is almost always the same one – a change at a specific spot in the gene. This makes diagnosis straightforward with genetic testing.

Most cases (about 80%) are not inherited from parents. Instead, they happen as new mutations during the formation of sperm or eggs. The risk increases slightly if the father is over 35 years old, but it can occur in any pregnancy. The overall incidence is about 1 in 15,000 to 40,000 births globally, similar in Nigeria and other countries.

How Is Achondroplasia Inherited?

Achondroplasia is an autosomal dominant disorder. “Autosomal” means it is on a non-sex chromosome, so it affects males and females equally. “Dominant” means only one copy of the mutated gene is needed to cause the condition. The normal gene cannot override it.

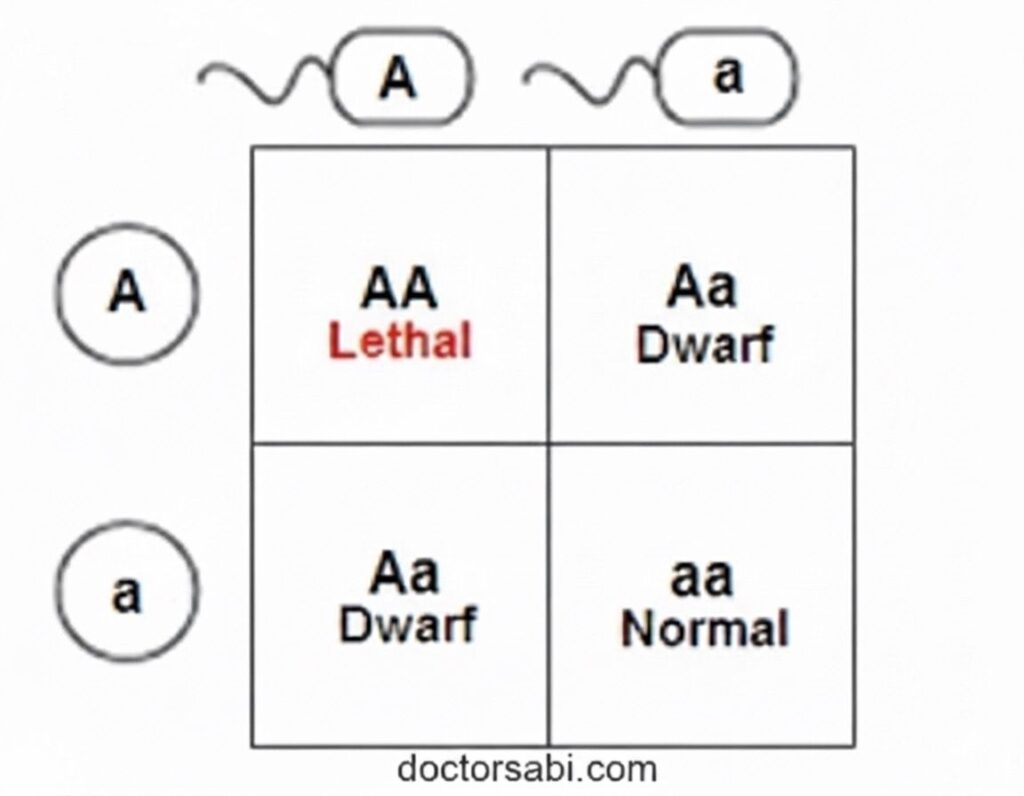

The Punnet square above represent the mutated gene as “A” (dominant) and the normal as “a” (recessive). People with achondroplasia are usually heterozygous (Aa) – one mutated and one normal gene.

The condition has 100% penetrance, meaning if you have the A gene, you will have dwarfism. There are no “carriers” who look normal but pass it on.

Inheritance When One Parent Has Achondroplasia

If one parent has achondroplasia (Aa) and the other is average height (aa):

- The parent with dwarfism passes A or a with equal chance.

- The average-height parent always passes a.

- So, 50% of children will be Aa (dwarfism), and 50% aa (average height).

This is straightforward. No lethal outcomes here.

Inheritance When Both Parents Have Achondroplasia

This is where it gets more complex. Both parents are Aa.

- Each parent passes A or a (50/50).

- Possible combinations for the child:

- AA (25%): Homozygous dominant. This is lethal. Babies with AA usually die before or shortly after birth due to severe breathing and neurological problems.

- Aa (50%): Dwarfism, like the parents.

- aa (25%): Average height, no dwarfism.

So, yes – there is a 25% chance for a normal-height child. But there is also a 25% risk of a non-viable pregnancy.

In practice, families report having children of average height. It does happen, though the odds are lower.

Visualizing Inheritance with a Punnett Square

A Punnett square is a simple tool to predict genetic outcomes.

- Rows: Mother’s contributions (A, a)

- Columns: Father’s contributions (A, a)

Results:

- AA: Lethal

- Aa: Dwarfism

- Aa: Dwarfism

- aa: Average height

This grid shows the 25-50-25 split clearly.

Other Types of Dwarfism and Variations

Not all dwarfism follows this pattern. Some are recessive, like spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, that needs two mutated genes. Others stem from hormonal issues, like growth hormone deficiency, which can always be treated.

Proportionate dwarfism (where the whole body is small) differs from disproportionate (like achondroplasia). Always consult a doctor for specifics.

Medical and Practical Considerations

If both parents have achondroplasia, prenatal care is crucial. Doctors use ultrasounds to measure fetal bone lengths by week 20. Genetic tests like amniocentesis can confirm the genotype but carry small risks.

For those wanting to avoid the mutation, options include:

- Adoption

- Sperm or egg donation from average-height donors

- Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) with IVF – testing embryos before implantation

In Nigeria, genetic counseling is available at teaching hospitals like LUTH in Lagos or UNTH in Enugu. Support groups like Little People of Nigeria offer community.

Health-wise, children with achondroplasia may need monitoring for spinal stenosis, ear infections, or sleep apnea. But many thrive without major issues.

Myths and Realities About Dwarfism

Myth: Dwarfism is caused by poor nutrition or curses. Reality: It is genetic.

Myth: People with dwarfism cannot have children. Reality: They can and do.

Myth: All children of parents with dwarfism will have it. Reality: As above, not always.

In cultures like Nigeria, stigma exists, but education helps. Focus on abilities, not height.

Final Thoughts

Two adults with achondroplasia can indeed have a normal-height child – with a 25% probability. But the pregnancy carries risks, so planning and medical advice are key.

Genetics can be unpredictable, but every child brings joy. If you are affected, seek support and celebrate differences.

Stay positive!

Useful Links

- MedlinePlus – Achondroplasia Genetics

- Mayo Clinic – Dwarfism Overview

- Little People of America – Family Resources

References

- MedlinePlus. (2023). Achondroplasia. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/achondroplasia/

- Pauli RM. (2019). Achondroplasia: A comprehensive clinical review. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-018-0972-6

- Horton WA, et al. (2007). Achondroplasia. The Lancet. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(07)61090-3/fulltext

- Savarirayan R, et al. (2021). International guidelines on achondroplasia management. American Journal of Medical Genetics.

- Cleveland Clinic. (2023). Achondroplasia in children and adults. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22183-achondroplasia